China is not exactly a popular investment destination these days. The China region Morningstar Category for US funds and exchange-traded funds saw its third straight year of net outflows in 2024. Meanwhile, portfolio managers with diversified mandates have shifted assets away from China toward India and other markets in recent years. As my colleague Francesco Paganelli recently pointed out, there are 50 funds and ETFs in Morningstar’s database with “ex-China” in their name, with an explicit mandate to avoid the market.

“Uninvestable” is a word you hear a lot these days for China. Reasons given include: “autocracy risk” stemming from the governing Communist Party, a disappointing economic recovery from the pandemic, property market troubles, a possible invasion of Taiwan, and demographic challenges. Oh yeah, and the threat of another trade war with the US looms.

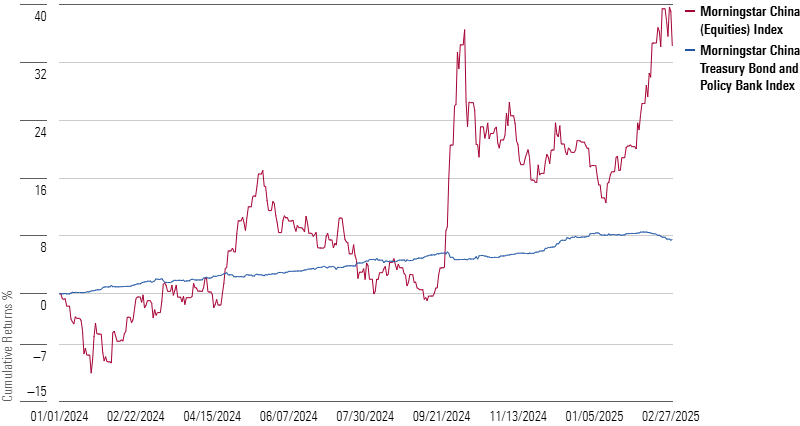

The thing is, while investor attention has been focused elsewhere, Chinese assets have actually posted strong recent returns. On the stock side, the Morningstar China Index advanced nearly 20% in 2024, then another 12% in the first two months of 2025. Bonds have also shone bright; the Morningstar China Treasury Bond and Policy Bank Index has recorded an annualized gain of 5% over the past three years in renminbi terms. Over that same span, the Morningstar US Core Bond Index is in negative territory.

The time feels right to dig into China and—as I discussed in last week’s column—emerging markets more broadly, given the bullishness toward the asset class expressed by many investment experts. Here, I’ll contemplate whether Chinese assets should be on investors’ radars. In the words of Hong-Kong-based researcher Louis-Vincent Gave on The Long View podcast, China is both a “super frustrating market” and “the most competitive economy that the world has ever seen.”

The Road to Uninvestability

When you stop and reflect, it’s amazing how dramatically the investment story around China has changed. In the years leading up to the pandemic, Morningstar analysts were writing about “China’s rise to prominence among emerging stock markets”; we were parsing differences between China A-shares, B-shares, and H-shares; and then-US senator Marco Rubio was going after index providers for adding Chinese equities to their benchmarks. At the end of 2020, the Morningstar Global Markets Index included Alibaba BABA and Tencent TCEHY as top 10 constituents. China’s 5% share of that broad gauge of equities surpassed that of the UK and Germany.

If you go back even further, of course, China was the “C” in BRIC. After the TMT—or technology, media, telecom—bubble burst in the early 2000s, the promising emerging markets of Brazil, Russia, India, and China became the trendy new investment theme. China’s economic growth was arguably the engine powering BRIC, given its voracious demand for Brazilian and Russian natural resources (India, a commodities importer, is a different story). In the first decade of the new millennium, China’s annual economic growth rate often exceeded 10%.

So, how did a rise that once seemed inexorable go off the rails? Well, first I’ll point out that China has been a difficult place to invest ever since the Shanghai Stock Exchange reopened in 1990, having been closed by the Communist Party in 1949. China is Exhibit A for the truism that economic growth does not always translate to financial market returns. In Chinese Stocks: The Road to Nowhere and Chinese Stocks: What Went Wrong, my recently retired colleague John Rekenthaler explored why capital-markets investors failed to profit from “the greatest economic advance in world history.” John notes a lack of corporate profitability, poor treatment of minority shareholders, weak legal protections, and a history of government intervention.

The last point was on full display in 2021, when the Chinese government came down hard—first on the for-profit education industry, then on Internet companies. Whether you call them “regulatory interventions,” “crackdowns,” or “kneecappings,” the outcome for investors was negative. The shares of New Oriental Education & Technology Group EDU and TAL Education Group TAL went into free-fall. Far more significant was the effect on the cohort of companies once known by the acronym BATS—Baidu BIDU, Alibaba, Tencent, and Sina—China’s answer to the US FAANG stocks (Facebook, now Meta Platforms META; Amazon.com AMZN; Apple AAPL; Netflix NFLX; and Google, now Alphabet GOOGL). Over the course of 2021, China’s share of the Morningstar Global Markets Index fell to 3.5% from a high of 5.4%. The much-anticipated IPO of Ant Group, an affiliate of Alibaba, was put on hold.

Remember that 2021 was also the thick of the covid-19 pandemic, which had originated in China’s Wuhan province. The government instituted tight lockdowns. Control also extended to business activities perceived to be contributing to societal problems. The for-profit education industry was said to put undo pressures on families, while issues with the Internet companies related to anticompetitive practices, data security, and content. In the eyes of some, China’s government was justifiably concerned about screen time. Others say it was about humbling outspoken business moguls like Jack Ma.

Whatever the case, China’s challenges only compounded from there. In 2022, Ukraine was invaded by Russia, with whom China shared a “friendship without limits,” in the words of President Xi Jinping. “Autocracy Is a Bad Investment” by my colleague Tom Lauricella articulated a view shared by much of the global investment community. In 2023, China ended its “Zero Covid” policies, and anticipation of a powerful economic rebound gave way to concerns over a deeply troubled property sector. Again, the government’s hand was visible, taking measures to curb excessive borrowing and speculation. Developers China Evergrande Group and Country Garden defaulted on their debt.

A Complex Picture

Befitting an economy of $18 trillion and 1.4 billion people, China is multifaceted, to say the least. When DeepSeek AI burst onto the scene in January 2025, it reminded the world of China’s technological prowess. Berkshire Hathaway BRK.A BRK.B fans know that the firm has long had a stake in Chinese electric vehicle manufacturer BYD 01211. In fact, Gave told us on The Long View podcast that China and its 130 carmakers lead the world in automobile manufacturing.

Gave credits the first Donald Trump administration’s trade policies for catalyzing Chinese industry:

“The leaders of China thought, well, if it’s semiconductors today, tomorrow it could be auto parts, it could be chemical products, it could be industrial robots, it could be turbines, it could be, you name it, it could be anything that we need from the rest of the world leaves us vulnerable to potential sanctions going forward. We thus have no choice, but to build our own industrial vertical in pretty much every single industry.”

Gave downplayed some of the risks contributing to the “China is uninvestable” view. He explains the real estate bust as stemming from the government redirecting bank lending from the property market to industry and notes it did not metastasize into a broader financial crisis. He calls China “probably the most competitive economy the world has ever seen,” citing the country’s trade surplus of more than $1 trillion. He calls the subject of an invasion of Taiwan “an overblown risk.”

‘Potential Upside Remains’

For their parts, the long-term value investors on Morningstar Investment Management and research teams see upside in China. “We are optimistic about the medium-term prospects for Chinese equities,” they write in the Morningstar 2025 Outlook. They expect stimulus measures initiated in 2024 to “continue evolving,” cite “a more benign regulatory backdrop,” anticipate “moderate earnings growth from Chinese companies,” and maintain a “positive outlook on several of the major technology firms as consumers regain their footing.” Indeed, Morningstar equity analysts see Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent as possessing wide economic moats, or durable competitive advantages that should protect their profits from competitive pressure.

It’s possible that strong recent returns out of China are just a cyclical upswing. Past rallies have lured in investors only to burn them. It’s also the case that falling Chinese bond yields reflect a slowing economy.

But perhaps as China slows, corporate profitability will become more of an emphasis. In my view, China could become a more compelling investment destination in the years ahead, especially if US equity returns moderate. It’s one thing to write off China when the US market is returning 25% per year; it will be harder to ignore if US assets struggle, as many experts forecast. I think the Morningstar 2025 Outlook strikes a nicely balanced view regarding investing in China: “Potential upside remains,” but “the road is likely to remain bumpy.”

Morningstar, Inc., licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. A list of ETFs that track a Morningstar index is available via the Capabilities section at indexes.morningstar.com. A list of other investable products linked to a Morningstar index is available upon request. Morningstar, Inc., does not market, sell, or make any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.