Everyone makes plans: for travel, fitness or the year ahead. China does it too. Last week, China’s top leaders met in a four-day conclave in Beijing to decide on the country’s goals and aspirations for the next five years.

Last week in Beijing, one of China’s most important political gatherings quietly took place. From 20-23 October, the Fourth Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) brought together the country’s most senior policymakers to discuss the framework of the country’s next Five-Year Plan (2026–2030).

Behind closed doors, senior officials reviewed the outcomes of the current 14th Five-Year Plan and debated priorities for the years ahead. A brief communiqué released after the meeting offered the first glimpse of the guiding themes of the 15th Five-Year Plan.

But what began as another episode of political volatility soon morphed into something else entirely. Buried in the data of Hyperliquid, a fully on-chain derivatives exchange where every trade is visible, investigators uncovered a position so perfectly timed it seemed impossible to be mere luck: a $1.1 billion levered short bet spread across and perpetual contracts, opened 30 hours before Trump’s post and closed almost immediately afterward for more than $150 million in profit.

Five-Year Plans: A Metronome of Modernisation

Five-year plans have long been one of the Communist Party of China’s key instruments of governance. The Central Committee, the Party’s main decision-making body, holds seven sessions between two National Congresses, each known as a plenum.

As is tradition, the discussions took place behind closed doors. The sessions were closed to both foreign media and domestic press, and delegates stayed on site until the meeting concluded. A short communiqué issued afterward provided a first indication of the direction of the next plan and the themes that will guide China’s development through the end of the decade.

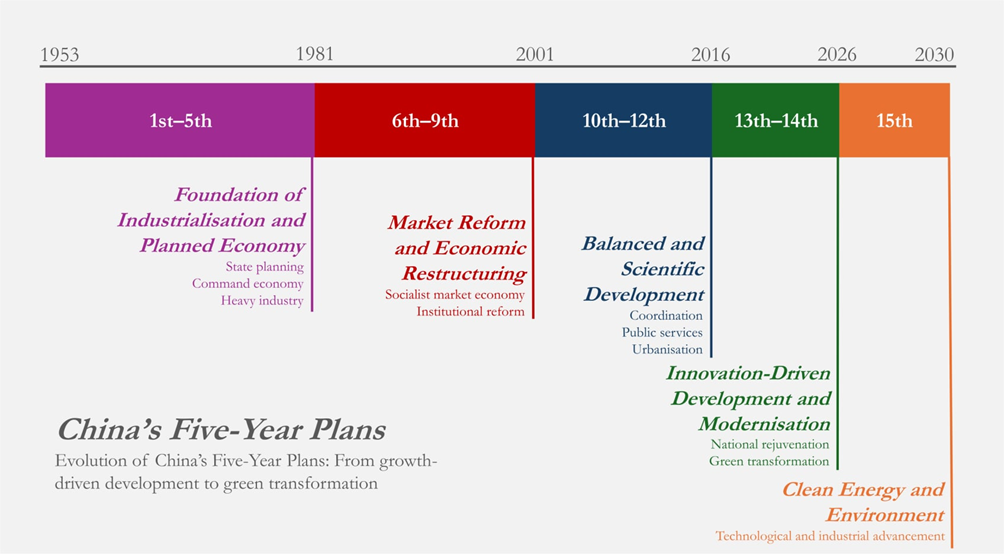

The Five-Year Plan has shaped China’s economic direction for over seven decades. The first plan, launched in 1953, sought to rebuild a nation still scarred by war and isolation. Inspired by the Soviet model, these early plans imposed production quotas and dictated the allocation of resources: steel, coal, and machinery first, consumption later.

Starting with the Sixth Plan (1981–1985), the term “social development” was added to its title, recognising that modernisation could not be limited to economic growth alone. Since then, each cycle has reflected the country’s shifting priorities: agricultural liberalisation in the 1980s, infrastructure expansion in the 1990s, and a transition toward innovation- and technology-driven growth in the 2010s.

Long before the final document reaches the Central Committee, consultations take place nationwide to capture public sentiment and practical needs. Between May and June 2025, an online campaign invited citizens to share their ideas. More than 3.1 million submissions were received. One post suggested using AI to monitor elderly residents to prevent accidents; another called for more local gyms, swimming pools, and badminton courts.

Once the Central Committee reaches its decision, however, the system’s hierarchical nature reasserts itself. The Five-Year Plan becomes the backbone of China’s economy, a guiding framework that ministries, provinces, and both state-owned and private enterprises must follow. It reflects the country’s defining traits: long-term vision and centralised governance.

Source: AustChina Institute

The 14th Five‑Year Plan (2021–25)

When China entered the 14th Five-Year Plan period in 2021, the global economy was still recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic. For Beijing, it was a moment to reset its priorities. Rather than chasing headline growth, policymakers introduced the concept of “high-quality development,” a vision first articulated by Xi Jinping in 2017. The focus shifted from how fast the economy grows to how that growth is achieved, through innovation, efficiency, and sustainability.

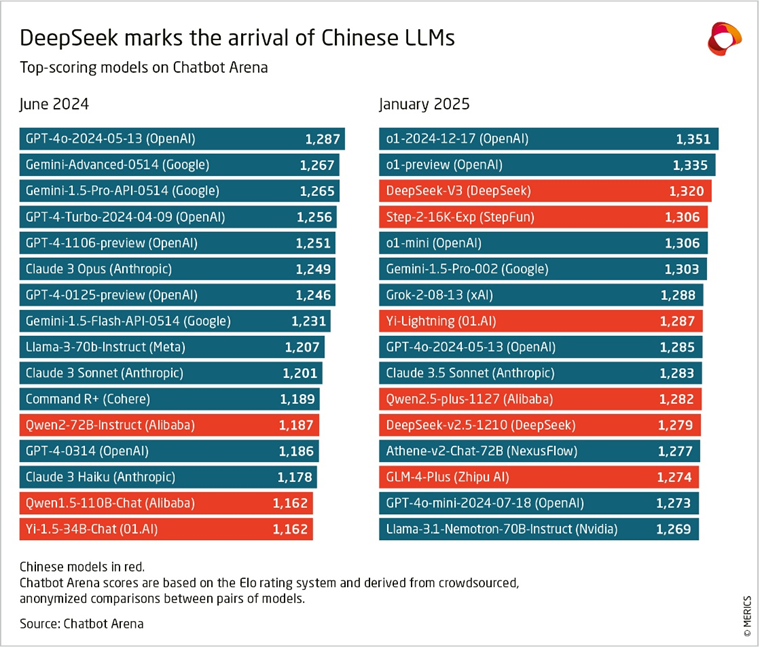

Over the past four years, this strategy has taken shape across every layer of the economy. China has consolidated its position as a global leader in clean energy, operating the world’s largest renewable power network and supply chain for green technologies. More than 6,000 factories have been officially certified as green producers, and the country now manufactures over 13 million new-energy vehicles annually. Its shipyards have mastered advanced vessels such as LNG carriers, aircraft carriers, and luxury cruise ships, the “three crown jewels” of shipbuilding. The same momentum is visible in technology. Success stories like BYD, Huawei, ByteDance, Alibaba Group and DeepSeek have propelled China into the world’s top ten innovators for the first time in 2025, according to the Global Innovation Index.

That trajectory has not been free of tension. Domestically, the property sector has gone through a sharp downturn. Major developers such as Evergrande and Country Garden have struggled with liquidity, leading to a slowdown in construction and housing sales. The crisis has strained local finances, already weighed down by pandemic-related spending and debt. Softer demand, high youth unemployment, and episodes of deflation have added pressure. Abroad, Western governments increasingly view China’s technological and industrial ascent as a strategic challenge, prompting tighter controls on Chinese technology and a series of trade frictions.

Economically, the 14th Plan marked the first time Beijing avoided setting a fixed growth target, instead it pledged to keep GDP “within a reasonable range.” Still, the long-term objective remains to double per-capita GDP by 2035. This requires an average annual growth of around 4.5 to 5%. Recent data suggest the GDP target remains within reach. Third-quarter figures show growth of 4.8% year-on-year and 5.2% for the year to date, suggesting that the country remains broadly on track to meet its medium-term goals.

The 15th Five-Year Plan (2026-30)

After a four-day conclave in Beijing, the Communist Party released Thursday a short communiqué confirming that the draft of the 15th Five-Year Plan (2026–2030) had been approved. The document described the geopolitical environment as “profound and complex,” but it made no direct reference to ongoing trade tensions with the United States. President Xi Jinping and President Donald Trump are expected to meet in South Korea at the end of October during the APEC Summit.

The communiqué offered only a broad outline of the plan’s direction. The complete document will be submitted for formal approval at the National People’s Congress in March 2026.

In tone and content, the communiqué reflects continuity with the 14th Plan. Nevertheless, some nuances stand out. The new plan places greater weight on building “a modern industrial system with advanced manufacturing as the backbone”, achieving “high-level scientific and technological self-reliance”, developing “a strong domestic market” and advancing the transition toward clean energy, as reported by Xinhua.

The report stressed the importance of preserving a solid manufacturing base while shifting toward a modern structure centred on advanced manufacturing. In recent years, Beijing has grown increasingly aware of the limits of its old growth model, built on property, infrastructure, and exports. One term “new quality productive forces” (“新质生产力”) dominates official speeches and policy documents. The focus is shifting toward new technologies, higher productivity, and scientific independence.

Over the past decade, China’s tech ascent has often depended on access to American innovation, including high-end semiconductors from companies such as . As US export restrictions tighten, Beijing aims to build a domestic ecosystem less vulnerable to external shocks and supply chain risks. The next plan is therefore placing heavy emphasis on breakthroughs in chip-making, quantum computing, artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and renewable energy, leveraging the country’s vast STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) talent pool to drive these advances. Artificial intelligence is one of the focus areas. Beijing is prioritising large-scale applications of AI across the economy, in manufacturing, logistics, healthcare, urban planning, and the fast-developing “low-altitude economy” of drones and robotics.

Under the next plan, policymakers aim to strengthen cooperation between state-owned and private firms and to expand the use of new technologies through an “AI+” approach. The Private Sector Promotion Law, introduced in 2025, gives private enterprises clearer legal standing and greater space to innovate.

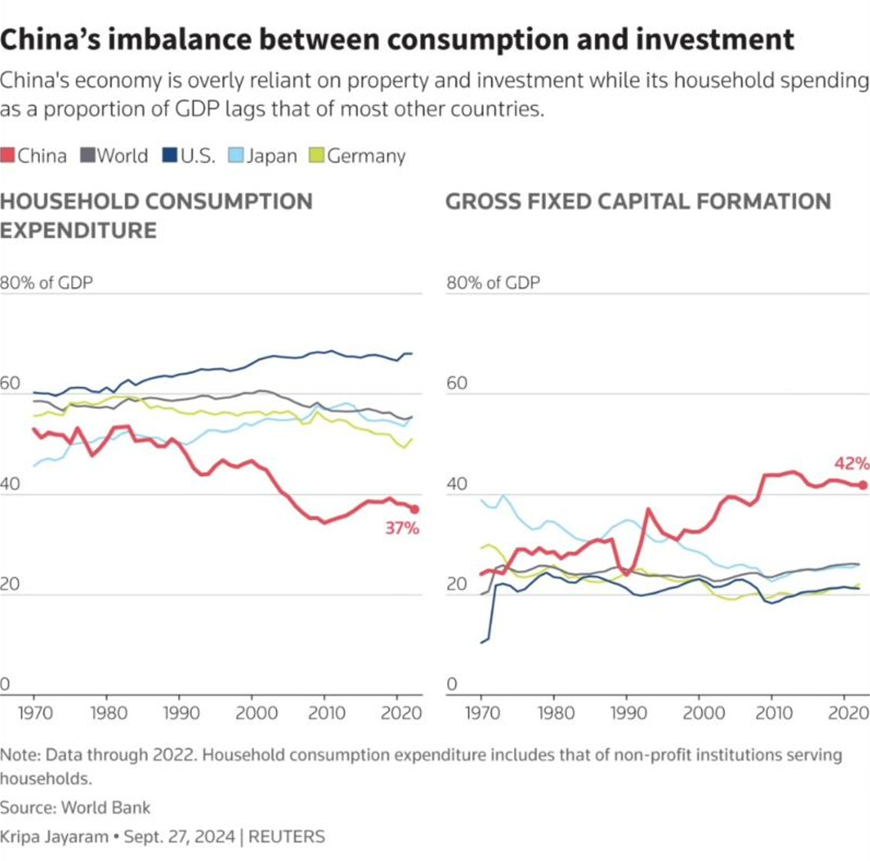

Regarding domestic demand, the new plan reiterates China’s long-standing goal of shifting the economy toward consumption-led growth, a priority that had often taken a back seat to investment and manufacturing. Yet, the proposed measures remain modest.

The communiqué calls for removing barriers to a unified national market and expanding both consumption and private investment. The new plan pledges to “increase efforts to guarantee and improve people’s livelihoods” and “improve the social security system,” as well as to “promote the high-quality development of the real estate sector.” Yet no direct fiscal transfers to households have been introduced, in contrast to the United States’ approach during the pandemic.

China’s economy faces a widening imbalance: investment accounts for over 40% of GDP, nearly twice the global average, while household spending lags around 37%, far below most major economies. Property prices continue to fall, precautionary savings exceed 20% of income, and deflationary pressures persist. Instead of tackling these structural weaknesses through income support, Beijing appears to be doubling down on its traditional playbook, infrastructure spending and state-led projects, in hopes of indirectly stimulating demand.

Compared to the 14th plan, the 15th Five-Year Plan marks a subtle ideological shift, emphasising bidirectional interaction between supply and demand. Policymakers now speak of “new demand guiding new supply, and new supply creating new demand.” Still, without bolder measures to restore household confidence and spending power, economists expect potential growth to settle around 3% annually if the imbalance persists.

Thursday’s session also saw Chinese leadership pledge to strengthen national security. The country needs to ” dare to fight and be good at fighting and bravely face major tests of high winds and waves and even perilous situations,” the statement read, though it offered no specifics. China’s expanding military capabilities have heightened friction with Washington and other Asia-Pacific powers. Beijing maintains that Taiwan belongs under Chinese sovereignty and hasn’t ruled out using force to take the island. The armed forces have recently undergone an extensive anti-corruption purge; nine senior military figures were expelled just last week. During the plenum, General Zhang Shengmin from the Rocket Force was appointed deputy chairman of the Central Military Commission, one of the nation’s most senior defence positions.

China’s leadership also pledged to ramp up environmental initiatives. While the country remains the largest emitter of greenhouse gases, it has simultaneously emerged as a global leader in renewable energy. The statement emphasised intensifying pollution control, speeding up the shift to a new energy system, and advancing toward carbon peak while promoting greener production and lifestyles. In September, Beijing announced its first-ever absolute targets for cutting greenhouse gas emissions, aiming to reduce overall emissions by 7–10% by 2035.

Conclusion

When the full plan is formally presented in March 2026, Beijing is expected to lay out specific targets for innovation spending, investment flows, and industrial transformation, steps toward a broader ambition. The 15th Five-Year Plan is more than just another policy cycle; it reflects China’s drive to transform from a manufacturing powerhouse into a global innovation leader, shifting from “Made in China” to “Created in China” and “Powered by China.”