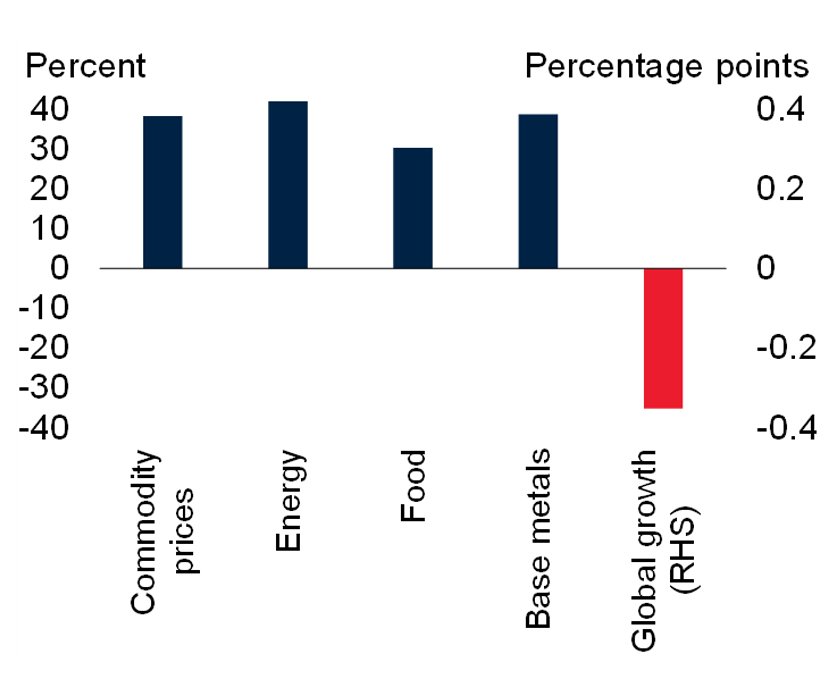

Global economic growth this year and next is expected to be nearly half a percentage point slower than the average in the half decade before the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet average commodity prices in 2024-2025 are predicted to remain close to 40 percent above 2015-2019 levels (Figure 1).

Prices of energy and food commodities, for instance, are expected to moderate but remain about 40 and 30 percent above their 2015-2019 averages, respectively. Base metals prices are set to rise slightly this year and next, averaging roughly 40 percent higher than in 2015-2019.

Figure 1: Higher commodity prices, weaker growth

Global growth and commodity prices in 2024-25, deviation from 2015-2019 averages

Sources: World Bank.

Notes: Deviation of the 2024-25 average for forecasts of global growth and World Bank indexes for commodity prices, energy prices, food commodity prices, and base metals prices from 2015-2019 averages. GDP growth forecast from the Global Economic Prospects, June 2024.

There are at least four forces behind this trend:

The global oil supply remains constrained. Since early 2023, Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)+ oil exporters have removed a substantial proportion of global supply from the oil market, progressively increasing and extending production cuts in response to perceived soft demand. As of late June, OPEC+ members were holding back more than 6 million barrels of oil per day—nearly 7 percent of global demand (Figure 2). This, combined with an increased focus on near-term profitability in the United States shale oil sector, which dampens the production response to higher prices, has supported higher oil prices. Brent oil has fluctuated between the mid $70s and the low $90s per barrel throughout 2024 so far. This pattern is broadly expected to continue into next year, with Brent forecast to average $79 per barrel.

Figure 2: Larger oil production cuts by OPEC+

OPEC+ spare capacity

Sources: International Energy Agency (IEA), World Bank.

Notes: Spare capacity for OPEC+ members as reported in IEA’s Oil Market Monthly reports. Other OPEC+ includes Algeria, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brunei, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Libya, Malaysia, Mexico, Nigeria, Oman, South Sudan, Sudan, and Venezuela.

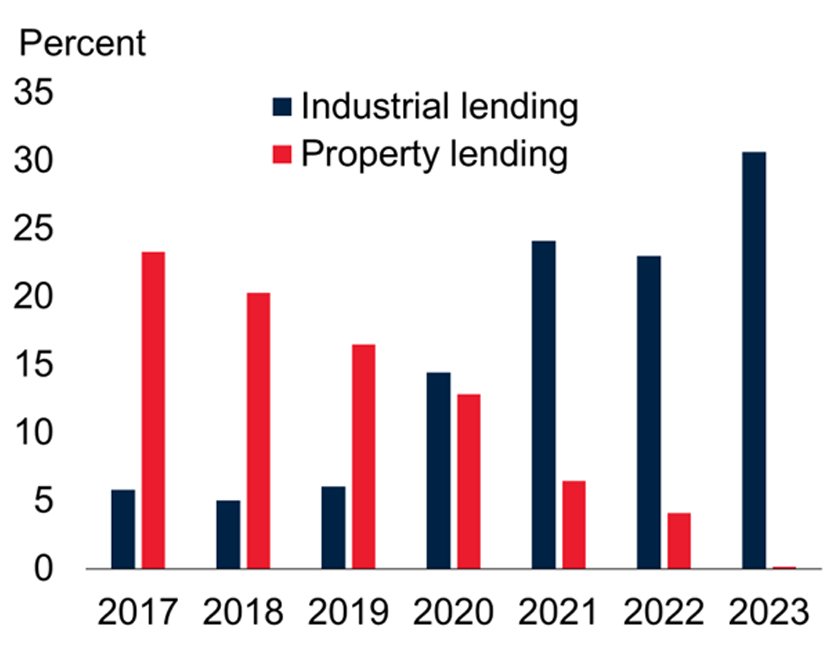

China’s demand for commodities has been resilient despite slower output growth. To a substantial degree, subdued global growth reflects a slowdown in China’s economy. This in turn partly reflects a downturn in the country’s property sector. In 2015-2019, China grew at an average rate of 6.7 percent annually. By contrast, it appears poised to grow at about 4.5 percent in 2024-2025. Excluding the 2020-2022 period, which was heavily influenced by pandemic-related developments, this would mark the slowest pace of growth in China in several decades. Because China is the world’s largest consumer of metals and energy, it was previously expected that a property-related slump would substantially reduce its appetite for commodities. So far, that has not happened. Instead, industrial commodity demand has proved resilient, buoyed by infrastructure investment and the country’s strategic focus on accelerating industrial capacity in preferred industries, including electronics and electric vehicles. That has at least partly offset commodity demand weakness emanating from the property sector (Figure 3).

Figure 3: In China, higher lending to industrial sector

Industrial and property lending in China

Notes: Annual growth of property loans and medium- to long-term industrial loans by financial institutions in China.

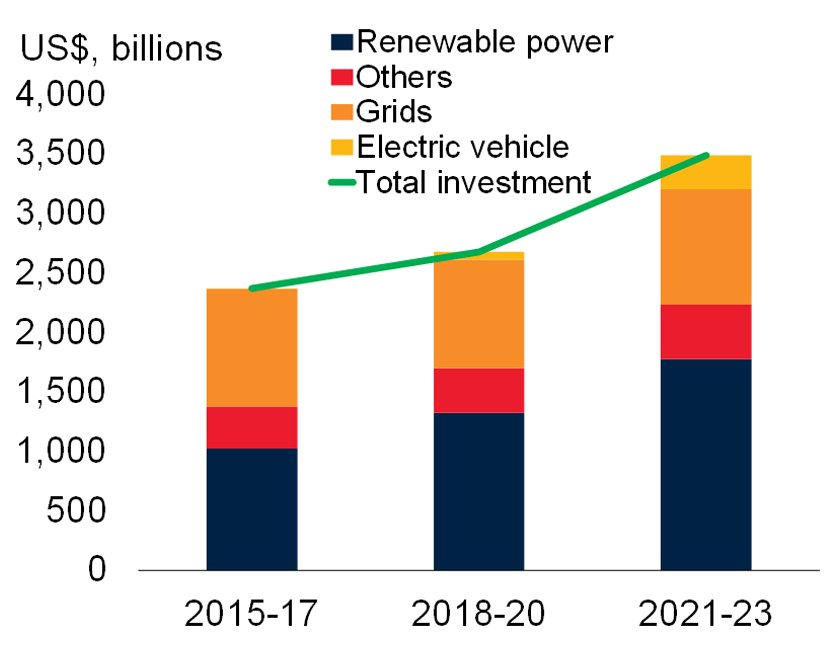

Climate change is driving metals demand and disrupting agricultural supply. The fight against climate change provides an increasingly important backdrop for commodity markets. Metals-intensive investment in clean energy technologies is growing at double-digit rates globally (Figure 4). This is generating strong incentives for expanded metals production, particularly materials such as copper and aluminum that are key to green technologies. Yet long lead times to bring new mines online mean supply is likely to remain tight for some time, which could keep prices of base metals relatively high. Meanwhile, in agricultural commodity markets, climate change-related weather events have recently crimped the supply of cocoa and coffee, driving prices to record levels. Disease- and disaster-related shortfalls are only likely to become more commonplace as temperatures rise and shift.

Figure 4: More investment in clean energy

Global clean energy investment

Sources: International Energy Agency; World Bank.

Notes: Total global investment in each three-year period in real 2023 U.S. dollars. 2023 values are estimated. Others = end-use renewable energy, electrification in building, transport, and industrial sectors, and battery storage.

Geopolitical tensions have intensified. Commodity prices have remained elevated and volatile in part due to geopolitical shocks over the past two and a half years. Having risen swiftly in 2021, commodity prices surged in early 2022 as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine destabilized energy and grain markets. After peaking in mid-2022, energy prices fell substantially. That decline, however, stopped from mid-2023, as OPEC+ oil exporting countries cut supply. The onset of the latest conflict in the Middle East then stoked geopolitical concerns, leading to price swings last October. In April this year, escalating Middle East tensions saw oil prices again surpass $90 per barrel, while gold prices, which are particularly sensitive to geopolitics, hit historic highs.

Going forward, geopolitical tensions remain a key risk to the outlook for both commodity prices and global growth, increasing the chances of further supply shocks (Figure 5). By some metrics, the number of active armed conflicts is already the highest in decades. Any conflict escalation that materially impairs energy supply could see broader commodity prices surge. In that case, global inflation could regain momentum, likely setting back the cautious monetary easing central banks are expected to undertake in the coming months.

More broadly, the combination of multiple armed conflicts and an increasingly turbulent geopolitical environment threatens to exacerbate uncertainty, dampen consumer and business sentiment, and fuel financial-market volatility. The historical record shows that heightened geopolitical risk is associated with weaker investment and large downside risks to growth. That makes it imperative for the global community to find a way to defuse tensions and redouble efforts to shore up the most vulnerable countries.

Figure 5: Heightened geopolitical risks

Geopolitical risk index, period averages

Sources: Caldara, Dario, and Iacoviello (2021), World Bank.

Notes: Average of monthly data, last observation is May 2024.

For now, higher commodity prices have opened up a crucial window of opportunity for commodity exporting countries. Now that prices have ratcheted up, many of them are expected to grow faster in the next few years than they did in 2015-2019. That gives countries a chance to reshape their economies in ways that can ensure long-term prosperity. A good first step would be to foster stronger institutions that can use revenue windfalls to rectify fiscal imbalances. They should also build foreign-exchange reserves and shore up central bank credibility.

As the global economy moves beyond the shocks of recent years and into the mid-2020s, several key factors intersecting with commodity markets and the growth outlook appear to have shifted. Weather-related disasters are becoming more common. Metals demand related to the energy transition is gaining steam. Geopolitical tensions have flared and show no sign of abating. Under these circumstances, a prolonged period of higher commodity prices amid subdued growth could become the norm.