Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Commodities myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

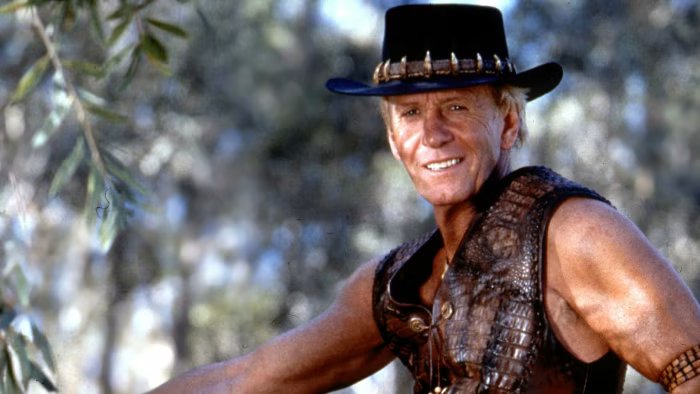

To paraphrase a commodity trading Crocodile Dundee talking to the denizens of r/wallstreetbets — “that’s not a short squeeze; this is a short squeeze”:

The London Metals Exchange has halted trading in three-month futures after prices leapt by 250 per cent (yes, you read that right):

Broken. pic.twitter.com/F1gnZD0ifw

— Neil Hume (@humenm) March 8, 2022

In this instance, the surge seems to be down to the inability of China Construction Bank, a big state-owned lender, to meet margin calls on a short position in the shiny, grey metal.

From Bloomberg:

The massive short squeeze in nickel has embroiled a major Chinese bank as well as the largest producer of nickel, according to people familiar with the matter. Chinese entrepreneur Xiang Guangda — known as “Big Shot” — has for months held a large short position on the LME through his company, Tsingshan Holding Group Co., the world’s largest nickel and stainless steel producer.

In recent days, Tsingshan has been under growing pressure from its brokers to meet margin calls on that position — a market dynamic which has helped to drive prices ever higher.

A unit of China Construction Bank Corp., which is one of Tsingshan’s brokers, was given additional time by the LME to pay hundreds of millions of dollars of margin calls it missed Monday. CCB International Holdings didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment, while Tsingshan representatives had no immediate comment on Tuesday.

The market for nickel, most of which is used to make stainless steel and which is also found in batteries and mobile phones, is not the most liquid.

Yet, while factors unique to this particular metal are clearly at play here, the inability of commodities market players to meet margin calls may be something that we see a lot more of. Which may, in turn, lead to broader funding pressures, as described by Credit Suisse’s Zoltan Pozsar in his latest missive which arrived in our inbox overnight (his emphasis):

Who drives the bid for cash, i.e. whose bid is driving term funding premia in this environment where lenders are less willing to lend cash for longer tenors? The commodities world, for three reasons. First, non-Russian commodities are more expensive due to the sanctions-driven supply shock that basically took Russian commodities “offline”. If you are a (leveraged) commodities trader, you need to borrow more from banks to buy commodities to move and sell them.

Second, if you are long non-Russian commodities and short the related future s, you are likely having margin calls that need to be funded. Anyone in the commodities world is experiencing a perfect storm as correlations suddenly shot to 1, which is never a good thing. But that’s precisely what happens when the West sanctions the single -largest commodity producer of the world, which sells virtually everything. What we are seeing at the 50 -year anniversary of the 1973 OPEC supply shock is something similar but substantially worse – the 2022 Russia supply shock, which isn’t driven by the supplier but the consumer.

Third, if you are short Russian commodities and long the related futures, then you are likely having margin calls too that also need to be funded like above. The aggressor in the geopolitical arena is being punished by sanctions, and sanctions-driven commodity price moves threaten financial stability in the West. Is there enough collateral for margin? Is there enough credit for margin? What happens to commodities futures exchanges if players fail? Are CCPs bulletproof?

As Zoltan puts it, Russian commodities have become the equivalent of collateralised debt obligations circa 2008. Non-Russian commodities, meanwhile, are like US Treasury bills — as safe as you can get. That growing disparity between core and “periphery” assets could, as was the case during the global financial crisis, provoke broader fears about liquidity and credit risk and lead to longer term funding drying up.

Events in the nickel market aside, broader funding pressures — while mounting — remain much weaker than they were during 2007/ 2008:

Cross currency basis in Euro (blue) and Yen (black) started widening out after fighting over a Ukrainian nuclear plant. So these first signs of Dollar shortage are NOT about CBR sanctions fallout. They’re about markets worrying war might run out of control and become global… pic.twitter.com/H4XxUDpRSn

— Robin Brooks (@robin_j_brooks) March 7, 2022

No doubt the trillions of dollars pumped into the system by central banks since 2008 is helping. But, if conditions worsen, then what’s the obvious a fix for the world’s monetary guardians this time around? Dollar swap lines with barrels of oil accepted as collateral? Or does Grandmaster Jay (or as Zoltan moots, the People’s Bank of China) need to become a full-on commodity market player?